“I knew as a kid I’d have to take care of it. I had prepared myself for it – for this moment,” Greg M., 41, says rather stoically of the overwhelming hoard that he inherited four months ago. Even so, “this is beyond what I thought it would be.”

In May 2010, Greg entered his childhood home for the first time in nearly 18 years. He’d driven the two-and-a-half hours from Burbank to his mother’s home in San Diego after she’d failed to answer the phone and missed a dialysis appointment. Greg figured something was wrong. Even though he’d stayed away from the house for years, he and his mother remained close.

When Greg knocked on the front door, he could hear his mother’s soft cries in the entryway. But he could not get in. The doorway was blocked – by his mother – and by stuff. He spoke to her through the mail slot then went around to the back door, prepared to break it down. “The door basically disintegrated,” Greg recalls. He then climbed over what had become mountains of clutter and possessions… through the kitchen… through the living room… and to the entryway, where he found his mother, collapsed, in a virtual air pocket. He struggled to get her out the door, to the front steps, where paramedics could treat her. Mrs. M., 83, a fun, feisty, and fiercely independent woman beloved by her neighbors… and, an extreme hoarder… would never return home again. For son Greg – an only child- the journey “home” was just beginning.

“The Project”

Shortly after his mother died, Greg took an indefinite leave of absence from his job in commercial construction to work full-time on cleaning up and clearing out his childhood home. He calls it simply “the project.” And he’s given himself six months to get it done. But truth is, he’s already falling way behind schedule. The scope of the project, as well as Greg’s reluctance to accept outside help, has made any sort of deadline near impossible to predict. “I have a feeling it might go longer than six months,” Greg concedes. “It might have to.”

Shortly after his mother died, Greg took an indefinite leave of absence from his job in commercial construction to work full-time on cleaning up and clearing out his childhood home. He calls it simply “the project.” And he’s given himself six months to get it done. But truth is, he’s already falling way behind schedule. The scope of the project, as well as Greg’s reluctance to accept outside help, has made any sort of deadline near impossible to predict. “I have a feeling it might go longer than six months,” Greg concedes. “It might have to.”

Despite tremendous progress, the house is still overflowing with a cacophony of items ranging from the valuable (a box full of nambé serving pieces), to the sentimental (a 1970s Christmas card from Grandma, with a five-dollar bill still inside), to the somewhat interesting (a pre-Snuggie “body mitten” still in its original package), to the worthless (expired medicine bottles, a bristle-less brush, drawers full of bottle caps) to the positively absurd and ironic (a “bless this mess” sign, stacks of unopened boxes of storage shelving, detailed logs of thrift store purchases and freebies).

Most of the trash is gone and there are pathways where before there were none. Greg is on industrial size dumpster number four, has donated about four tons of clothing, and collected five small dumpsters of recyclables. But it’s like a teardrop in an ocean.

Most of the trash is gone and there are pathways where before there were none. Greg is on industrial size dumpster number four, has donated about four tons of clothing, and collected five small dumpsters of recyclables. But it’s like a teardrop in an ocean.

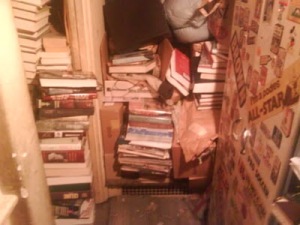

Thousands of books balance precariously in dust-laden stacks in what was his father’s study… bags and bags of crafts that his mother bought from a Native American bazaar line the living room floor… a guest room known as the ‘orange room’ for its orange carpeting, orange bedspread and orange drapes is – quite literally- filled to the rafters in what looks like an over-crowded time capsule from the 1960s and 70s. An old tape recorder sits atop the pile and Greg ponders what to do with it. He remembers trying to show his father exactly how it worked. “I was a little embarrassed that he didn’t know. I mean… he was such a brilliant man, very smart, couldn’t figure out how to use an old school tape recorder,” Greg recalls with some dismay. The wheels are in motion in Greg’s head. The tape recorder is obsolete. But it holds memories. He has trouble putting it down or letting it go – despite the specter of corroded batteries leaking out the back. Greg places it back on the pile. It’s a “keeper” item, at least for now.

Greg had to hire a locksmith to even get into that orange room. He doesn’t know how long it had been sealed off, or why. The answer may lie somewhere – buried in the hoard.

Greg figures his mother hadn’t gone upstairs in at least two years – because of her frailty and because of the blockade that had formed along the stairwell. Not that it mattered, he says. The whole upstairs had become “just storage.”

“It Was All I Knew”

In Greg’s early years, the 2400 square foot, two-story house with a large garage and sprawling backyard was filled with life, and only hints of clutter. The kitchen, living room, formal dining room, bathroom and study on the lower level, as well as a master bedroom, guest room, bathroom, and “Greg’s room” upstairs provided plenty of room for a family of three to function, and entertain. But as Greg got older, his parents started drifting apart and his mother’s penchant for collecting, and thrift shopping, and saving, and storing spiraled out of control.

Greg started noticing the change when he was about 10. His mother saved everything – even dental floss containers. She was convinced that they could be gutted and used to store things – really small things – and she had a whole bag of them. There were also bags of pen caps and plastic lids. All meticulously labeled.

The hoard grew as Greg did – and he learned to live with it. He stayed at the house until he was 23. “You’d think as soon as I turned 18 I’d get the heck out,” Greg says with a knowing sigh. “I don’t know why it took me so long to get out. I guess it was all I knew. This was the only house I’d lived in. So perhaps I was scared – and comfortable here. Even though it was a mess, it’s what I knew.” But it came at a price. “Living here at the house, it affected me, y’know, in not being able to bring friends over, especially in high school, friends, girls, there’s always the embarrassment factor, having to make up stories why I couldn’t have people over. And as a kid, just always [being] self-conscious either home or out in public to the point of being paranoid. My folks would always wonder, ‘why do you think people are always watching you? Why do you think they’re always looking at you when we’re out in public?’ Well, cause I knew the secret at home.”

When Greg left home in the early 1990s, there was no looking back. From that point on, “going home” meant going as far as the driveway, or meeting up with his parents at a local restaurant. “I don’t think I ever said the words ‘I’m not coming back until it’s cleaned up, or improved, but I think it was understood,” Greg recalls. “And then towards the last few years, my mom didn’t want me in ‘cause she was embarrassed. She knew how much worse it had become and also she didn’t want my criticism… She got to a point where she basically would start crying when I pushed too much.” So Greg stopped pushing. “She didn’t want any help from me, any other family, or friends, neighbors…. Everyone understood there was nothing I could do, as much as I wanted to,” he says, with a small catch in his voice. “I had to let her live the way she wanted to. But actually if I knew it was as bad as it was, I may have intervened.”

“He, Too, Became a Hoarder”

Greg’s mother was a registered nurse who retired when Greg was born. His father was a high school English teacher for 35 years. They were well-liked, intelligent, active members of the community. But they never sought help for the hoarding. “I don’t think they saw it as a problem,” Greg says, and perhaps they enabled each other. “[Dad] went to garage sales to buy books. [Mom] went to garage sales and thrift stores to buy schlock and clothes and what-not.”

Greg says his mother suffered from depression and other mental-health issues that may have contributed to the hoarding. “I think I recognized stuff as a kid and as a young man that I now know is like [Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder] type of behavior, perfectionism, moodiness. My dad on the other hand, he never showed any signs. He was quite stoic and quiet.” But still, he was not immune. The study, where he spent most of his time, grew to resemble a used-book warehouse. “[When I was] a kid, the bookcases were full, but not stacks of books everywhere. So he too became a hoarder.” The dusty enclave that was his sanctuary had to impact his health. “He had respiratory problems,” Greg says. “He had quit [smoking] for the last few years of his life but I’m pretty sure the air quality in the house was not good for him.” His mother also battled a myriad of physical ailments over the years, including heart problems, osteoporosis, and cancer. “I’m sure the conditions in the house did not help matters with her,” he says. And as a retired nurse, “you’d think she’d be aware of the health risks involved with hoarding.” Evidence shows the couple shared the house with a bevy of dust mites, spiders, bees, and rodents that found ample hiding space amid the hoard.

Outside the house, Greg’s mom was considered a petite powerhouse. “Everybody loved my mom,” Greg says fondly. “She had more energy than any of us. She was well-loved, involved in many organizations, volunteered much of her time. A very colorful person [with] vibrant, colorful clothing. You wouldn’t know that her house was the way it is if you met her on the street. And even people that did know, they accepted it and liked her for who she was.”

In recent years, Mrs. M. was forced to slow down as her health took a turn for the worse. When Greg found her in the entryway last May, he knew it was the beginning of the end. He also knew that the state – and fate- of the house would never be discussed. “I didn’t [bring it up] because her health declined very quickly and I didn’t want to give her any stress. I knew she didn’t have long. Days, maybe a week,” Greg says. “What was there to discuss? I mean, I suppose I could have asked her ‘Why – why it got to this point’, but she was having trouble talking. Her voice was very hoarse, it was hard to hear, so um…” The words trail off as Greg struggles to answer a question that lingers still. “She’s tried to make her peace in the past – apologized for certain things, but the house never came up.”

“I Have Not Grieved”

Greg loved his parents, but he hasn’t been able to grieve for them. “I have not grieved for my dad who died four years ago, nor have I grieved for my mom. My dad – I don’t know why. I guess I knew there was still the house to deal with. There was something basically bigger than the two of them that I had to deal with. I haven’t felt the need to grieve. I want to though. I want to grieve, I want to cry, but I have this house to deal with,” Greg says with a frustrated glance toward the cluttered home. “I’m hoping that will happen. I don’t know when. Maybe when the house is done. Then maybe I’ll be able to grieve for my parents. Then I may miss my parents.”

The Storage Units

Greg had braced himself for the job at hand. But his parents’ hoard was not contained to the house itself. The backyard had become a jungle of overgrowth mixed with trashcans, plastic containers and a shed filled with more “miscellaneous” things. Inside the garage, a washer and dryer sat buried under more random stuff – including several unopened boxes of yet-to-be-assembled storage shelves, various papers and small appliances, old campaign posters, and even an egg carton filled with rocks labeled “Wisconsin rocks 1979”. Among many other things, Mrs. M., a native of Wisconsin, liked to collect rocks.

And then there were the off-site storage units. Greg knew his parents had one, and a few years ago, he asked his mother for a look inside. She showed him four. One belonged to his dad. It was filled with books – thousands of them- and a couple of filing cabinets with paperwork from his teaching and union days. The other three belonged to his mom and were jam packed with random stuff. “All I saw was newspaper, junk, who knows what. They were so full she couldn’t even look over the piles,” Greg recalls. He and his mother discussed strategies for clearing them out and donating items to charity, but they failed to reach agreement on how to go about it. Stalemate.

“I knew it wasn’t going to happen, so I let it go. I said, ‘Well, I’ll have to take care of it when the time comes.’” When that time arrived, Greg returned to the storage facility and was hit with another devastating surprise: There were actually six storage units, not four. Not surprisingly, the storage facility managers were sorry to hear about Greg’s mother. She was a favorite customer. “Their six units were costing them roughly 700 dollars a month,” Greg says. “And for what value? I don’t think any of it was valued at 700 [dollars].”

In some ways, the storage units were easier to deal with than the house itself. “I started with my dad’s unit. That was the most basic. I just boxed up books, got ‘em ready for pickup, recycled anything in there and trash, and had it picked up for donation, all the books. That was the easy unit. The others – my mom’s units – I rented a UHaul truck and proceeded to just empty ‘em out. I didn’t have time to sort. But I did bag up clothing and various items, knick-knacks, for donation.” That’s not to say Greg got rid of everything. He kept the smallest of the units, filling it with items that he wasn’t quite ready to let go of. “Sentimental stuff, things of value, whether that value is monetary or ‘other’. And that can be sorted through, processed, at another time. But I have to watch myself. I don’t want to become a storage ‘person’ myself.” Greg’s goal was to rent the unit for one month. That was three months ago.

“I Could Be a Hoarder”

Back at the house, Greg’s progress has slowed in recent weeks as “the project” gets ever more personal. The living room chair in which his mother often slept remains untouched – with a slightly dented pillow still capturing rays of sunlight peeking through the curtains. His mother’s colorful array of hats and shoes remain scattered throughout the house. Stacks of pots, pans and dishes – some clean, some not – align the kitchen counters. Greg has forged a path into his old room, but he’s saving the bulk of what’s in there – for now at least. “This is where my progress in the house slowed down, for the most part, cause I came across a lot of sentimental [things], whether it be toys or just anything – anything I remembered.” The closets and drawers remain full and untouched. “The rest of everything in here I need to go through, need to do the final processing,” Greg says, “[to] see what I’m gonna keep.”

In the hallway outside his room, a shelf is stacked with a hodgepodge of things that Greg has collected from various spots upstairs and doesn’t want to lose track of. Among them: decades-old books and photos, a McCalls Magazine from 1966, boxes and bags of costume jewelry, Christmas items, coins — and even old clothes tags. “[My mother] has an envelope of clothes tags of mine purchased in 1972. This is an example of the stuff she kept. I don’t know why I held onto this but for the…” Greg stops to think, and rationalize why it hasn’t gone into the trash. “This is a look into her mind I guess.” And perhaps, into his as well.

“I have recognized these tendencies are…” The words trail off. “I could be a hoarder. But that’s another reason I’m going through this process the way I am, so I don’t become one,” he says, well aware of the challenges ahead. “I’m still in the ‘trash, recycle, donate’ phase. It’s when everything that I want to keep is here in the house… Do I just keep it?… Or would that be like hoarding, cause there’s a lot that I’ve kept. I need to go through it. I need to clean this house and get it to a point where it can be lived in.”

The Girlfriend

Though Greg is an only child, he does have someone else to consider in the equation of his life and the house that has recently consumed it.

He’s got his own house, 120 miles away, that he shares with his girlfriend of 13 years, Sidney. She says Greg has an issue with clutter – especially paper – but that he’s done a good job keeping it in check and respecting their home. It hasn’t been easy, and now she’s got a better idea why.

Sidney knew and liked Greg’s parents – for all intents and purposes, they were her in-laws — but she never saw their house. “I don’t remember specifically when Greg told me that his parents were hoarders,” she says. “I did think it was odd we could only meet them out for lunch instead of going to their home to visit. He finally just told me, ‘The house is a wreck. That’s why I left. And they don’t want me [to go] in, I don’t want to go in, and I certainly don’t want you to go in.’”

Sidney got her first glimpse inside the house shortly after Greg started “the project.” He needed to clear a path before he would – or could- let her in. “I didn’t have any expectations,” she says. “It didn’t smell, like I thought it might… but just the enormity – the mass, the sheer mass” was overwhelming. “I didn’t go upstairs the first time. It wasn’t clear.” And she couldn’t begin to fathom how Mrs. M got around. “She was very petite, even when she wasn’t sick- I don’t know how she did it. I don’t know how she got to the fridge or the microwave, I don’t know. Greg did notice in the fridge the leftovers from the last lunch we had with her. So she got there, I just don’t know how she did it. Willpower I guess.”

“The project” has been a double-edged sword for Greg and Sidney. It’s put a definite strain on their relationship. But it’s also brought some issues to the forefront that needed to be addressed, including Greg’s disposition to hoard. “That is a bright side of this project,” Sidney says, “[Greg] seeing this (she motions toward her in-laws’ house) in himself. That doesn’t mean everything’s fixed at once but there’s an awareness that maybe wasn’t there before.”

“Hoarding Is Selfish”

Sidney tears up when looking at Greg’s “inheritance”. She is mad at her in-laws, for what they’ve done to Greg and to their life together. “The irony is [that Greg’s parents] were saving this for him,” she says. “Every little baby bottle, every little scrap, every rock that you see. In their minds they were doing it for him. And it’s just turned into this beast… I look around and there’s so many things that I guarantee should be a no-brainer [to get rid of]. But [Greg] doesn’t see that yet.”

That’s not to say that Greg isn’t angry with his parents too. “I think hoarding is very selfish,” Greg says. “For them to collect all this stuff and they know they’re gonna pass soon, and leave it… yeah, that’s been frustrating me a lot with this project,” he says with a deep sigh. “Even if I had many siblings, it wouldn’t be fair.”

The house is paid off, but the cost of “the project” has been adding up in terms of money, lost wages, physical and emotional strain, and precious time. Eighteen years after leaving home, Greg’s parents’ big secret is once again his. “It’s been a secret whether people knew it or not. It’s been painful. Not having people over. Having to make up stories… It’s just something that’s inside that doesn’t go away. I’ve had this in the back of my head, probably thought about it every day my whole life. And I knew this day would come.”

The Future

Life has been on hold since “the project” began. Greg is four months and counting into what was supposed to be a six-month project. And he’s still reluctant to accept outside help. “I wanted to do this by myself. And I think I’ve always had that in my head since I’ve been planning for this for so long. I have the need to touch everything… I need to see what it is, what all this hoard is. I don’t want help cause then [others would] be going through stuff that I want to go through. Yeah, I can tell them what’s trash, what’s not. But I want to see those items. I want to get my hands on them. I want to go through every box. Cause this is my life… I’m doing it for possibly selfish reasons by myself, but I think it’s therapeutic,” Greg says with a somewhat defensive sigh. “I just need to see everything myself. And I want to make the decision what happens to each item.”

Where does that leave Sidney? “I just kinda have to stand back and let him succeed or flounder,” she says. “Hopefully succeed. I want to see him succeed.” But “I need some milestones and timelines stuck to. I can just see this being a constant uphill battle never finishing. I don’t want to be a part of that. [In a] perfect world, we’d get this fixed up and move down here and find jobs down here. But – my biggest concern is that there won’t be any finality to this.”

Sidney’s been keeping a blog documenting Greg’s progress and hopes it might help others in similar situations. “If you think you’re a hoarder,” she pleads, “look around, get some help, because you’re really hurting the people you love.”

As for Greg, he’s taking it one day at a time, one object at a time. “When I was younger I always said I’d never live here again.” Now he’s not so sure.

Note from the author, Hannah R. Buchdahl: I interviewed Greg for this story in September, 2010, four months into “the project”. He later discovered three additional attic spaces – all full. In the years that followed, Sidney and Greg broke up and Sidney died before we had a chance to reconnect in person (see sidebar). I’ve lost touch with Greg, for now. Status of hoard – unknown.